Analyzing exfiltration routes on Solana

We recently saw the largest crypto heist of all time. Hackers cashed out millions from the $1.5 billion ByBit hack.

For criminals who hack, they need to turn stolen assets into spendable cash and that too without detection or as low detection as possible.

In practice, it is difficult to do so with any 1 technique.

So they build laundering pipelines out of multiple techniques. Each step mixing or obscuring the trail.

For example, a typical chain of moves might be

Swap stolen SOL or tokens on a DEX

Break the proceeds into many small transactions

Bridge funds to another blockchain

Mix them through privacy tools

Funnel into centralized exchanges (CEXs) or off-ramps.

Let's unpack each of these strategies using real cases and public on-chain data so that the defenders can stay one step ahead.

(if you are interested in only the possible paths and the amounts the hackers can take, then please have a look at the example section towards the end of the report)

Cross Chain Bridge Based Exfiltration

A common tactic is to bridge stolen funds off Solana immediately after the theft. Bridges don’t demand identity checks, so they “break” the chain between the stolen tokens and their true origin.

For example, during one hack the hackers moved $500 K of USDC from Solana to Ethereum in five chunks using a TWAP-style streaming swap, then into Bitcoin through Thorchain.

But why do launderers bridge out?

Bridges such as Wormhole have high liquidity linking Solana with over 21 blockchains like Ethereum, BNB Chain, Avalanche and more. So the thieves can mint wrapped ETH, BTC, or other tokens without any identity checks.

Because bridges like wormhole tap into shared liquidity pools across ecosystems, they can handle tens of millions in a single transaction. Wormhole’s daily volume are in millions. This shows how much value can flow through without manual oversight.

A Typical Multi-Hop Laundering Path

Now say the bad actor has $1 million. They will split it into a few smaller transfers across multiple bridges or wait for quieter periods on-chain to avoid slippage and reduce the chance of triggering alerts.

Often, a thief will send SOL through Wormhole to mint wETH on Ethereum, swap that wETH for Bitcoin on an Ethereum DEX, and then bridge the BTC onto the Bitcoin network for final cash-out.

Each hop adds complexity, since no single ledger ties all the swaps together in one place.

While this is traceable, it becomes difficult to trace in a short period of time. By using more than one bridge and spreading transactions across different chains, hackers make tracing their trail a slow, frustrating task for investigators.

After bridging to the new chain, they often mix (more on this in later sections) or wash the coins in services like Tornado Cash so it’s hard to see where they came from (e.g. 14 500 ETH from the 2022 Nomad hack went into Tornado Cash in $2 M tranches).

Centralized Exchange Based Exfiltration

Platforms such as CoinEx, Gate.io and Bitget let you swap Solana for bitcoin, ethereum or other tokens.

Laundered crypto still flows through CEX, and a handful of platforms handle the bulk of those illicit funds. The situation was so bad that just 5 exchanges handled about 68 % of all crypto cash-outs by illicit actors in 2022.

While the large players follow strict anti-money laundering laws, it is important to know their addresses for any immediate actions to be taken. The addresses many CEXes as well as other methods are linked to a Google sheet at the end of this report.

But why CEXes?

Bad actors often lean on centralized exchanges because they offer deep liquidity and direct fiat off-ramps.

Source: Messari

Even when platforms require KYC, many controls can be bypassed. Criminals slip through with fake IDs or mule accounts. Some CEX have looser identity checks in certain jurisdictions. Criminals exploit these gaps by creating dozens of accounts under slight variations of the same fake identity.

What are the next steps usually followed by them?

Rather than deposit $1 million at once, a launderer will split it into many $50k trades across different accounts and times. This is called “smurfing” and it avoids triggering internal alarms for unusually large transfers.

Hackers repeat this not just across accounts but across several exchanges. Each handoff breaks the on-chain link to the original stolen funds. Then they often use mixers (see next sections) or OTC trades (see next sections) to finish the cleanup.

By hopping between multiple exchanges, they turn one big theft into dozens of “normal” customer trades.

From Centralized to Decentralized Exchange Based Exfiltration

Savvy criminals also launder using non-custodial DEXs.

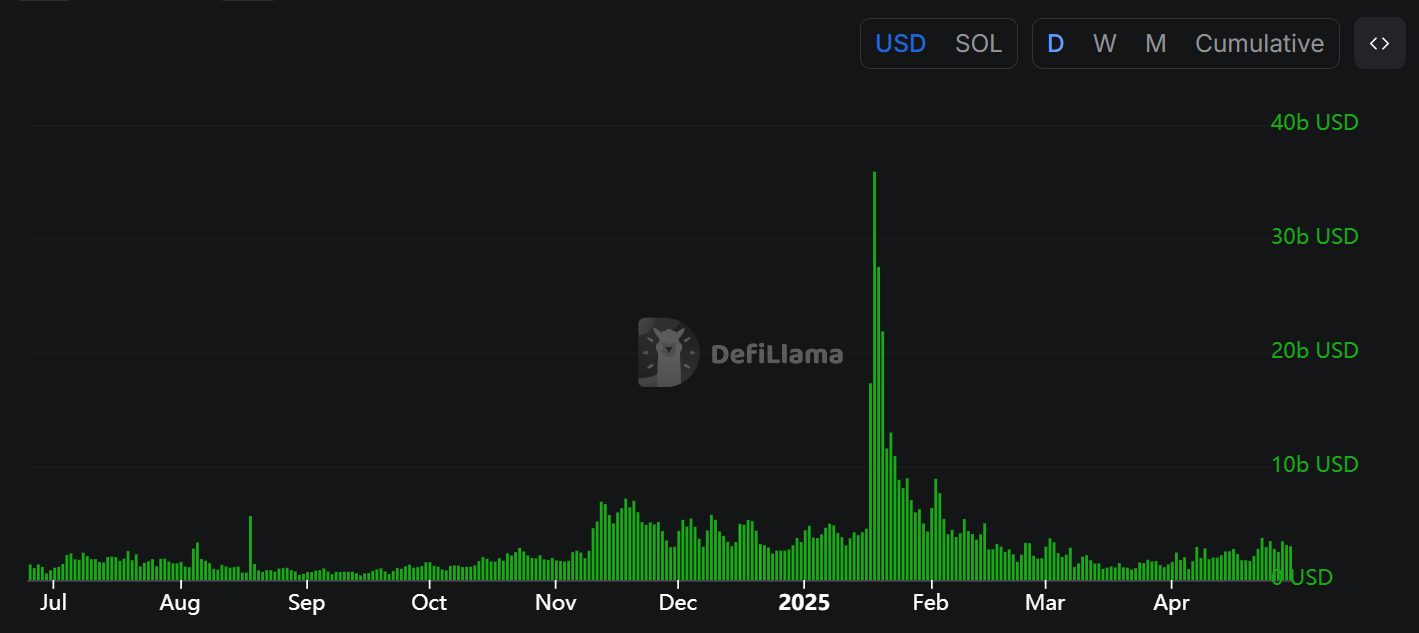

Solana’s DEX ecosystem moves huge sums every day to the tune of multiple billions in trading volume across all chains in a single 24 hours.

Raydium, Orca, Saber and others power on-chain swaps with no middleman

Aggregators like Jupiter route trades across multiple AMMs for the best price

Source: DefiLlama

The Possible Paths: How Funds Get Obscured

Swap Stolen SOL for stablecoins (USDC), wrapped tokens (wETH) or even memecoins.

A major SOL/USDC pool on Raydium holds around $8-$10 million in liquidity, letting you swap up to a few million with only modest slippage.

Niche pools can be under $100k in liquidity, so big trades there would move markets and stand out.

They can also fragment the trades across different pools big ones and small ones to mix the trail. This is traceable onchain, but the sheer volume makes it difficult for the good actors to act quickly.

Cross-Chain Bridges like wormhole and deBridge add extra layers of complexity.

The Bybit Hackers followed a similar path.

OTC Desks Based Exfiltration

Over-the-counter (OTC) desks like Wintermute, Jump Crypto are private brokerages where two parties negotiate large crypto trades directly. There is no order book. And because these trades happen off the public order book, they leave fewer on-chain traces.

They are often linked to big exchanges but they also operate independently.

Why Criminals may use them?

Massive Liquidity. OTC desks can routinely move millions per deal and some brokers process billions in volumes each month.

No Public Footprint. Because the deals happen privately. There’s no on-chain transaction linking buyer and seller, just the final deposit or withdrawal.

Weaker KYC. In some gray markets, OTC “banks” run by syndicates issue their own stablecoins or private exchange rails to skirt formal checks.

Steps usually followed in OTC Exfiltration

Attackers often recruit OTC brokers through darknet forums or private chat networks where criminal vendors advertise laundering services.

Because OTC trades leave little trail, launderers pair them with fresh wallets or mixers. Funds exit the desk straight to brand-new addresses or into mixers breaking on-chain links.

TRM Labs reports that Lazarus Group’s Bybit hack proceeds which are over $400 million in Bitcoin were staged for large-scale liquidation via OTC networks after cross-chain swaps and mixers.

What about the Deal Size?

Even mid-tier OTC brokers can handle millions per deal with minimal slippage.

Syndicates string together dozens of brokers, easily moving hundreds of millions in a single laundering operation.

P2P Exchange Based Exfiltration

Peer-to-peer marketplaces connect buyers and sellers directly, using escrow services rather than public order books.

Players such as Paxful can be used where users deposit crypto and release it once they confirm receipt of cash or bank transfers. Even large exchanges like Binance have built P2P sections.

How Will Bad Actors Use Them

Many criminals prefer P2P because there’s no centralized trade history to shift through.

They will split large sums into dozens of smaller deals. Typical on-chain P2P offers under $100 k per counterparty to avoid scrutiny

Often meeting in person or via Telegram groups. So each of transfer stays below exchange reporting thresholds. Much P2P can happen off-platform as well. Avenues such as Telegram channels, “SOL for cash” regional chat rooms and WhatsApp groups or local dealer contacts.

Those trades settle directly between ordinary user wallets, making them look like routine peer payments. By spinning trades across dozens of wallets, launderers can clear millions over days or weeks.

Mixers

Crypto mixers are privacy tools that break the connection between sending and receiving addresses.

Mixers work by pooling tokens from many users together, then redistributing them to different addresses. Think of it like everyone putting cash in a box, shuffling it, and taking different bills out. The blockchain still records all transactions, but the mixer obscures who sent what to whom.

People use mixers for legitimate privacy reasons (like hiding wealth from potential thieves) and sometimes for less transparent purposes but it also is being used by the bad actors.

So how they use it?

After crossing blockchains, funds move to mixers like Tornado Cash, which has laundered more than $7 billion since 2019.

After on-chain mixing, criminals often bridge to Ethereum or BNB Chain and swap into privacy coins like Monero through centralized or instant exchanges. Makes it difficult to trace back to the original hack.

This adds another layer as on-chain activity on Solana looks like a normal bridge, and on the receiving chain the Monero swap hides further links.

There are few players on Solana such as Ghosty and Aintivirus which enables anonymity.

Memecoins as Mixing option

So Memecoins on Solana are also being used as impromptu mixing pools:

Attackers mint a new token, deposit stolen SOL to trade for that token, and then wash-trade it across multiple wallets to muddy the trail.

How the hackers abuse it?

Step 1: Create a token. The thief may use platforms like Pump.fun to mint a fresh token (say “SHIT2069”).

Step 2: Seed it with stolen funds. They send large chunks of stolen ETH or USDC (bridged to Solana) into the new token’s bonding-curve account. That inflates the token’s price.

Step 3: Dump for clean coins. They trade (via Jupiter, Orca, etc.) back into SOL or USDC. On-chain it looks like normal token sales, not a direct hack.

Step 4: Repeat across tokens. By cycling through a half-dozen launches in quick succession, they layer the funds.

Pump.fun and similar launchpads see batches under $1 million pool liquidity. So enough to hide mid-range thefts but not mega-heists.

Funds Movement Example for $1 million

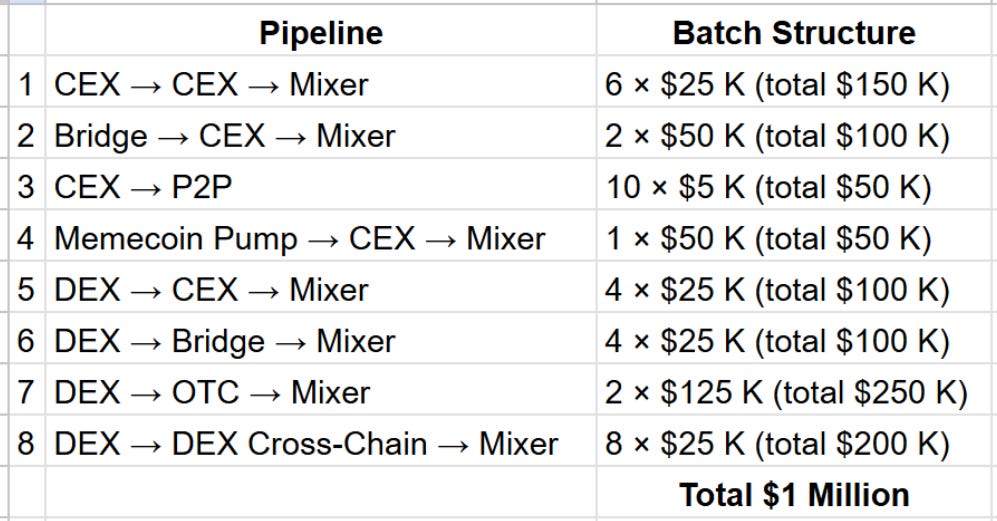

Okay so we saw all the various paths a hacker can take. Now lets see a representation of 8 sample paths the bad actor will take for exfiltrating the $1 million.

1. CEX → CEX → Mixer

Stolen coins go into a central exchange in Six equal chunks of $25 K. From there, they move to a second exchange to confuse the link. Finally, the funds enter a mixer to scramble their origin

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $150K

Remaining: $850K

2. Bridge → CEX → Mixer

Assets are sent through a cross-chain bridge in two $50 K transfers. The bridged tokens arrive at a central exchange, and then feed straight into a mixer. By splitting into a few mid-sized batches, this blends with normal bridge traffic before the final wash.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $250K

Remaining: $750K

3. CEX → P2P

Ten small transactions of $5K to a P2P service provider.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $300K

Remaining: $700K

4. Memecoin Pump → CEX → Mixer

A single $50 K wash-trade kicks off on a niche token launch. Profits swap to non-freezable assets and hit a central exchange. From there, the funds enter a mixer to erase on-chain history.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $350K

Remaining: $650K

5. DEX → CEX → Mixer

Four $25 K swaps on a decentralized exchange into non-freezable assets. Those assets then land at a central exchange and then funneled into a mixer.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $450K

Remaining: $550K

6. DEX → Bridge → Mixer

Four $25 K trades on a DEX swap SOL for USDC, then go through a bridge to another chain. After bridging, the tokens flow into a mixer.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $550K

Remaining: $450K

7. DEX → OTC → Mixer

Two $125 K swaps on a DEX, then an OTC desk buys the tokens off-chain. The desk credits the hacker’s account, which then sends crypto into a mixer.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $800K

Remaining: $200K

8. DEX → DEX Cross-Chain → Mixer

Eight $25 K swaps hop through two different DEXs using a bridge. After moving between networks, the funds end up in a mixer.

Total Funds Exfiltrated so Far: $1M

Remaining: $0

That’s the sample path a hacker may take to exfiltrate the funds using these routes. I have also identified Wallet addresses related to some of the exfiltration routes and the Non-Freezable assets that may be used by bad actors.

Addresses & Asset Details

Wallet addresses related to Exfiltration routes

Google Sheet - Tab 1 https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1OaeamUg8bPCl96YNXa1tyJsLtAa1p-5iIi39KnODWyU

Non-Freezable assets which may be used by bad actors

Google Sheet - Tab 2 https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1OaeamUg8bPCl96YNXa1tyJsLtAa1p-5iIi39KnODWyU/edit?gid=187614475#gid=187614475

Hacker wallets not tagged on Range

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Is0Q3IT4EeZtcnAEyQU25nics3TDlEFgSVOWWJNDzx4

References

https://intel.arkm.com/

https://www.antiriciclaggiocompliance.it/app/uploads/2025/03/The-2025-Crypto-Crime-Report-Chainalysis.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://defillama.com/bridge/wormhole

https://www.slowmist.com/report/2024-Blockchain-Security-and-AML-Annual-Report(EN).pdf

https://solscan.io/

Thank you for reading. I hope this educational piece on Exfiltration routes in Solana is worth your time. If you have any suggestions or want to discuss more, I am reachable on X & Telegram - @its0xRay